|

Proportion

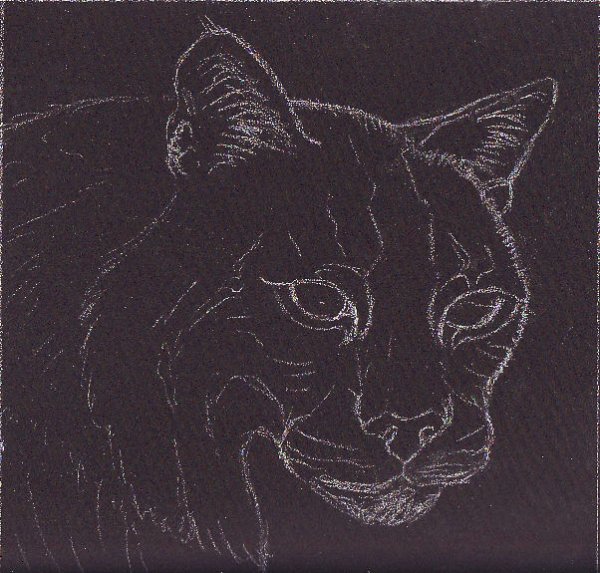

Proportion is essential to representational art. My bobcat sketch above was drawn freehand looking at a photo, because I've had a lot of practice sketching cats and painting cats. All cat heads have some similarities and this bobcat isn't far from my cat's facial structure. The more often you draw the same subject, even in different poses, the more familiar and accurate you become, so draw what you love most. Any beginner who wants to do representational art runs aground fast on something ugly about proportions. The mind sees what it thinks is there, not what’s really there. Eyes come out drawn as pointed ovals with a round iris kissing top and bottom and a pupil in it -- an icon of an eye rather than a realistic eye. On top of that, beginners can sometimes get the details right but draw a different feature an unrelated size. One eye may be much larger than the other and lower on the face. One ear may be placed right, the other one hovering on the top of the head. Very often beginners also place the start of the drawing badly on the page. I can’t count the number of times I drew good faces and got the features right in a good relation to each other... and cut off the top of the head with the edge of the page because I didn’t account for the whole size of the head. I felt better about it when I joined an art workshop with many beginners and saw every one of them do the same thing. Not to mention that bad habit that I still need to break of always drawing right out to the edge of the paper. I forget that I need to leave at least 1/4” of margin from the edge of the picture, in order to mat it and put it in a frame. So there’s my first suggestion for proportion. Open up your sketchbook or pad, and mark off lines at least 1/4” smaller than the edges of the sheet. I usually like to make them larger than that and go for standard sizes, like 8” x 10” in a 9” x 12” sheet so that if I take it out to frame it, that’ll fit in a standard size. UK and other European artists may be doing this with the A sizes or metric. Just make a habit of marking those guidelines on any blank page before you start. They are very useful and they will give you a basis for several different ways of measuring proportion on anything you draw. Anything.

Rule of ThreeThe old composition guideline of “The Rule of Three” can also be a proportion aid for placing elements in a picture and drawing them accurately. Choose units, inches or metric, that are easily divided by three until you’re used to it, say a 6” x 9” picture area. Mark up that rectangle on your paper, doesn’t matter if it’s tall or wide. Then mark off each side with two marks outside the margins, at the 2” and 4” marks on the short side. Then at the 3” and 6” marks on the long side. You don’t have to draw the lines across the paper to see that it divides it into a grid of nine rectangles. You can just lay the ruler across it or use a thread or rubber band held down with push pins on your drawing board. The four crossings of those imaginary lines are four great focal points. If the most important part of the picture is on one of those crossings, the painting will look better and far more professional. Not all good compositions use the Rule of Three, but any painting that does usually gets a good composition. What they also do is divide the area into nine rectangles. That makes a simple grid, allowing you to use Grid Method for proportion accuracy.

Grid MethodThis works better with photo references than it does from life, although Renaissance painters and Old Masters would sometimes make a proportion tool for live models to sit for their portraits. A glass window in its frame would be marked off with a carefully inked grid of squares and mounted on a stand the artist put between himself and the model. He could then mark the canvas with a grid and draw just what was in each square of the grid at a time. This breaks down complex images into simple ones. You can tell where the one curved line of the top of the head enters that grid square and where it leaves it. Getting the curve right on that is much simpler than remembering where on the page the top of the head goes, so you get it right. Patiently copying what you see one square at a time works miracles. Try this at home. Use inches or two centimeter squares. Do it with something same-sized in a photo reference. Print it out in black and white so you can easily see white, black and gray areas. Mark off an exact six by nine grid on the picture, or as many squares as will comfortably fit (full squares). Mark off your paper with that many squares. This is why to use your usual measurement system and do things same-size the first go. Then go across the top or down the side just drawing exactly what you see in that square and making sure the changes from dark to light are placed right on the edges of the square. Connect them up as you go. It takes a while to do this but it never fails to astonish anyone who's got proportion problems and never tried it. The results are near-miraculous. There is only one drawback to this method. It takes erasing the grid lines on your paper after you get the good drawing done. I hated those grid lines. I could never erase them completely. Much later on, I bought a lightbox and that solves the problem -- you can make a grid on tracing paper, tape that to your lightbox and tape your paper over it carefully. Wow, no erasing. Mine is the Artograph LightTracer, an inexpensive lap-sized model that's good enough when I want to copy a sketch. Other artists found Grid Method wonderful and had a lighter hand with a pencil than I do. They were able to erase easily even when a line ran across a white area. If you don't have a light box, draw the grid lines so lightly you can barely see them so that they're easier to erase in the white spots. If you just get tired of gridding, you can use the other traditional method of getting proportions right. It's related. I thought I invented it but then I ran into mentions of Tick Marks in several different art books.

Tick MarksStart from another photo reference printed out in black and white. You can even play with it in Gimp to reduce it to just flat black and bright white areas by raising contrast till you have a Notan before printing it out. That makes either of these proportion methods easier because you'll wind up with a contour drawing outlining the white and black areas. Mark off the picture area on the reference exactly, say, 6" x 9" since we used that for the Rule of Three example. Make sure the reference is blown up big enough that it fits in there with some space around it. For finesse, you can cut a 6" x 9" window in a piece of cardboard or mat board and move it around on the reference till it looks good, then draw inside it with a pencil. Pick out an important single point on the photo reference. I always started on faces with the inside corner of one eye. Using your favorite ruler, measure across the reference to that point. I use a grid ruler to make sure it's lined up at an exact horizontal to the picture. Mark that on the top by putting another straight edge at a right angle to it. Then measure it again in the vertical, put another ruler or straight edge across it and mark that on the right or left. I would do all my tick marks meausurements against the same side, just choose one and stick with it. The second straight edge doesn't need to be a ruler, it can just be a clean strip of cardboard with a machined edge. You now have coordinates for the first Tick Mark. Measure down from the top and in from the side to the same place on your paper and make a small light dot. Then do the same thing with the outside corner of the same eye. Then do that with the inside corner of the other eye, then its outside. They now make some sense and are placed perfectly, when you draw the eye shape between them it'll be the right size. Don't stop there. Measure the lowest part of the eye itself and put its tick mark. Do that again with the highest part of the eye and any point where the eyelid curve changes direction. Until you're used to drawing eyes accurately, the more careful tick marks placed lightly to describe the shape, the better it'll look. Do four of them for where the iris meets the edges of the eyelids, that's another good placement set. Start doing tick marks for every part of the face that changes direction or has a dramatic contrast. Bottom of the chin, lowest part of the bottom of the chin. Top of head. Sides of face. Top of ear. Bottom of ear. Hair edges where they change shape, especially if hair is fluffy. You won't just get the general proportions right. You'll get every feature shaped right too and exactly placed where it belongs in relation to everything else. You wind up with something that's like a Connect the Dots picture. The first time I did it, I was disgusted at the bad proportions of my attempts to draw a famous actor. I'd get his features right and no two eyes the same scale. So I did about 400 tick marks on that first one. I got him right, not only his general proportions but the exact shape of every feature. Wow. It rocked. It was awesome. Every time I did it, I cut corners and used a few less Tick Marks until now I use maybe half a dozen to get someone's facial proportions. Top and bottom of head, place the inside corners of eyes, place the corners of the mouth and I'll get whoever it is right. That's if I don't just look and sketch what I see -- but I spent years doing life drawing as a street artist where I could not use Tick Marks on live people who only had half an hour of patience to be drawn. I had to come up with something else. Of course I reinvented something artists have been doing so far back that it's as old as the oldest jokes.

Rule of ThumbOut on the street, when you've got a box of oil pastels, a pad and a willing tourist waving money, you can't use Tick Marks and you might have trouble carrying that Grid Window with you to your setup unless you make it very light and put it on an expensive tripod. Mind you, the grid window would be a serious attention-getter if you want to do street portraiture. Instead, you'll need to just look at someone and get their proportions right on the first go. At least close enough that you can fix it before they see what you're doing. The oldest ruler in history is your thumb. Those cartoons of artists holding up their thumbs in front of someone they're drawing are showing a real technique. You know the distance of your arm. You know the distance between your knuckle and the tip of your thumb. You hold it up next to the face. You can see that it'd take maybe three and a half thumb joints top to bottom of head and that's what you sketch on the paper, using your thumb as a guideline. It takes a bit of practice. You can also use a pencil or a long handled paintbrush as the measuring tool. Marking off a few handy points on it by putting rubber bands around it creates "joints" for different measurements. Practice this at home with various objects you draw from life. Hold your arm out and look at the fridge -- mine is a half height dorm fridge, and it's three whole thumbs top to bottom. The front door is two thumbs wide. I wouldn't make it long and tall by mistake. This sloppy Rule of Thumb method is very good for subjects you're already familiar with. You don't need to measure the exact length of the lady's eyelashes and their angle the way you would doing either Tick Marks or Grid Method with her graduation photo for a detailed portrait. What the Rule of Thumb is best for is quick sketches.

Blocking Out SketchesThis is a method of establishing proportion that most artists use and I never did. I honestly never took to it -- that erasing thing again. In most art courses there is a long sequence of drawing cubes, spheres and cones. Then you learn to break down the human body, or the cat's body, or a tree or anything into cubes, rectangles, cones, cylinders and spheres. You draw these as they are, semi-disconnected but the right general shape and then refine them, erasing the ugly box lines of the cube that encases the hips and the cube that encases the ribcage connected with the cylinder of the waist that makes that sketch look like C3PO until erased and refined. Personally, I don't like drawing and erasing unnecessary lines. Most artists who do use blocking in as a preliminary stage will do so on a preliminary sketch and then copy it rather than erase all those lines. I've seen that time and again. It varies. How hard is it for you to erase your lines? Blocking in is a shortcut to proportion that has some serious advantages. It means you're not using 20 tick marks to describe one eye. You're using one eye line running through the pupils of both eyes to get them on a line with each other that is at right angles to the center line of the face -- which may be at a tilt. Tilted faces are asy to get wrong because the mind wants to straighten them out. What I did instead was sometimes just turn the drawing so the face was straight on to me and draw it before turning the drawing right side up to see it at its tilt. I find myself doing a little blocking in now, not in the classic geometry-to-accuracy proportion method but reducing my sketches to simple lines as I started that bobcat sketch. I did the cat's ear first, with cats I tend to start with their ears. I placed his other ear in relation to it and sketched the curve of the neck going back from the first ear and the line of the side of his face next. I eyeballed proportion from the ear to the cheek, got that right by rule of thumb, then proceeded to get the shape of the muzzle. I had a coloring book outline of a cat for my first round. I placed the eye on the right (cat's left eye) by eyeballing it in relation to the corner of the ear above it and in from the side of the cheek. I could have laid a pencil across the reference and slid it up to see where on the cheek bulge the eye was. I've done cats so many times that when I was doing the cheek curve I mentally noted "that's where the cat's eye height is." I was imagining that grid ruler in place, approximating where I'd put Tick Marks if I had been taking my time with a printout to be perfectly accurate. Lately I have been deviating from references more and more as I get more skilled, making changes on purpose so as not to violate a photographer's copyright. That is more advanced, it comes later on when you're used to the proportions of a type of subject like cat faces or people. Rule of thumb extends to imaginary lines and seeing proportions in relation to each other without an exact measurement. That only comes from practice and life drawing. I would have been doing this with cats years sooner if cats were the ones paying me $25 a sketch on the streets of the French Quarter. Here's another proportion trick that can help either in life drawing or deciding where to put your Tick Marks. Draw from the Negative Space. Negative SpaceBefore I drew that bobcat sketch, I drew the space around the bobcat. I followed the edge of what was cat and what wasn't cat, using cat parts as landmarks. This can be a wonderful way to avoid misproportioned cat parts or anything else. It also means you can have your line width in the background color if you're doing it on the spot in color. I could have put my cat into a forest and taken a dark green oil pastel to skitter along just outside the line of the cat's neck (noting where it falls up and down on that nine-patch imaginary grid of the Rule of Three) and continued around the ears (where is the highest point in relation to the edge? How close to the Rule of Three line?) to the cheeks. I was doing that throughout because the Rule of Three is the easiest grid to imagine. When you draw the outside of something and get that line accurate, its jigs and curves and changes of direction in the right position, the proportions of everything inside it are easier to place. I knew where to put the inside corner because I already had that side of the ear placed right where it met the bobcat's head. I knew how far up the muzzle changed direction because I imagined those lines crossing the sketch. I then decided to make it square and chopped 1 3/4" off the right and 1/4" off the left just on how that negative space looked, giving it a better intuitive composition. I violated the Rule of Three, just moved my ruler till it looked good. I wouldn't have seen to do so if I hadn't got that outside line just right and the cat's head sized well for the space.

QuickComp as a Proportion ViewerLong after I got used to imagining those lines, I ran into a handy little gadget at Blick and ordered it on a whim. It's very convenient. Blick actually carries the Durer grid -- one of those clear gridded windows you can put in front of a still life setup or your squirming child to have Grid Method without tattooing the person. QuickComp is much cheaper. It serves the same purpose though. It's a stiff plastic piece 6 1/2" x 8" with two horizontal and two vertical lines drawn at thirds on it. Look through it and anything you look at is lined up to judge Rule of Thirds on. It's also broken up into that nine patch imaginary grid so that you can sketch fast a section at a time. This doodad is handy, it's just under $10 and I wish I'd had it as a beginner. It would've made gridding a lot less eraser-intensive -- it's easy enough to just mark the points on the outside of your lines for thirds and keep moving the ruler around. One artist in an online video marks off the halfway points between the thirds as guides but doesn't draw the lines. So there are ways of adapting Grid Method that don't involve drawing the grid -- just knowing where it is. You can make a QuickComp for yourself at home with a big enough sheet of heavy clear plastic from the packaging of something that had a clear plastic window or the bubble-pack has it on the back. Just take your salvaged clear plastic, cut it to 1/2" larger than a standard picture size, tape heavy black thread on the thirds points and frame that with black electrical tape. You can also make something like a QuickComp without the plastic by using black string or thread and taping it into a cutout in a piece of mat board. Black matboard is good for this, it looks better and you can use electrical tape to fasten the thread. Or just go ahead and get the QuickComp, it's up to you how frugal you want to be. The homemade version has the advantage that you can do it to several different proportions -- cut a mat opening the size of the picture you want to do and construct it to those proportions. You might want to do something 6" x 12" and have the thirds points at 2" and 4" instead of the middling proportions of the QuickComp itself. Great for doing wide panoramic landscapes.

Tricks for scaling up or downWhether you use Grid Method, Tick Marks, your thumb, a QuickComp or any combination of those measuring methods, scaling a large view down to a small picture or a small reference up to a good size drawing is going to take a little basic math. Or not, depending on how you do it. One thing you can do to reduce the math is use easy proportions like "twice the size" or "half the size." Things easy to calculate. One of my tricks was to use the metric side of a ruler on a small reference and then turn each centimeter into an inch on the drawing. When those won't do, there are some other handy drafting tools that can help. I used to own a proportion wheel. It was a round plastic set of wheels with numbers on a spinner with a little window that showed the measurements if I had it dialed to the right proportions. I used it a lot because I was a typesetter and the print shop always had them laying around. One that was especially handy, which I still have, is an architectural ruler. Those three-sided rulers have six different scales. I learned to remember which scale I used on the picture and which one I used on the drawing and just turned it or rolled it to the other one after counting off units. If you use an architectural ruler like that, mark on the reference what a unit is and mark in the margins of your drawing what a unit is. That way you won't get mixed up if you have to stop working on it and go back to making tick marks again later. Of course if you are fast at multiplication, you can pick an odd figure like "blow it up by 4.5 times" and just do that in your head as you go. I'm not that fast or good at it, so I'd use mechanical aids. Each their own. The main thing with scaling up and down is to have a size of units for the grid or tick marks on the reference and a different size unit for the one on the page. Centimeters to full inches is usually good for most smallish references but this could even be centimeters to feet if you're sketching for a mural. I would do a smaller drawing of the mural design before gridding it onto the wall if I did.

Practice is the best guide to proportionI'll end on this even though I mentioned it so many times. The more often you draw the same thing, the better you understand its proportions. You will remember where the eyes fall on a human face somewhere between the dozenth face and the hundredth face, to the point where you can distinguish a person whose eyes are a little close together or a little high or low. Much as I love cats, there was a time when my attempts to draw them sometimes looked like dogs. I could not believe their muzzles were that short, especially when it wasn't a Persian. I didn't see the shape of their foreheads well either and sometimes elongated their heads like an Afghan hound's. Not to mention how long it took to learn to draw a rose that wasn't just a spiral on a stem. Roses are hard until you get them. Roses were much harder than human faces when I got right down to it. I think I had to draw more roses to get them right than I ever did people. Their proportions change depending on breed and how far along they are in blooming. The buds are easy but anything beyond a bud started to look grotesque and wound up boxy, sort of bent in the middle and distorted. This is another reason for gesture drawing, blocking in and sketching in general. If you do a dozen sketches in twenty minutes, each of them was another chance to concentrate on seeing the right proportions and getting them down on paper. If you spent twenty minutes sketching it, you'd add shading and detail but you might be shading and detailing a blocky gob with a spiral on top instead of a rose. If you spent three days drawing it in supreme detail and getting all the colors right when its proportions were off, you might wind up looking at a strawberry ice cream cone with leaves instead of a rose. Yes, I have done this. Many more times than I could count. Today, I can draw roses that look like roses. Don't ask me about sweet peas unless you've got a picture of one I can sketch from. Even at that, it'll look better if I do it a few times scribbled and sketchy than if I were to try to do it carefully with all its details the first time. So use up those sketchbook pages. Use cheap oil pastels and do the same thing over and over in different ways. Keep it simple. One reason oil pastels are so good for this is that they are thick like crayons. You'll get the color and value accurate but it takes a lot of work to drag out any significant detail. A quick sketch with them will be bold and simple -- and good proportion will make that look cool even if it doesn't have much detail. So draw what you really like, something that never bores you. It could be shiny motorcycle parts, it could be naked ladies, it could be roses and violets, it could be mountain streams tumbling over rocks, big cats lounging on rocks or twisted dead trees. At various times all of those have been favorites of mine. Just keep on sketching and when you get a good one, copy it larger for a more detailed version.

|